U.S. Unemployment by State -- Benefits, Status and Implications

Want to know why we still have high unemployment despite a record number of job openings? Just read to the end.

Jobs Are Everything

Jobs are everything to the economy and the ultimate source of effective demand (purchasing power) for residential and commercial real estate. Period. Good news is that the U.S. had a record 9.3 million available positions according to the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) as of the end of April 2021, a monthly data release from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Yet as of June 2021, the U.S. unemployment rate ticked up to 5.9 percent from the 5.8 percent in the prior month.

Full Employment Defined

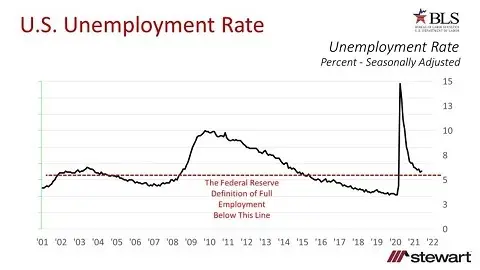

The Federal Reserve defines full employment for the U.S. when the unemployment rate ranges from 5.0 percent to 5.5 percent, or less. Using this definition, the U.S. was fully employed in the four years prior to the onset of the pandemic in 2020 as shown in the graph below. The unemployment rate exploded from a 51-year low 3.5 percent in February 2020 (also reached in September 2019 and January 2020) to 14.8 percent in April 2020 just 60 days into the pandemic.

Historical Unemployment Rates

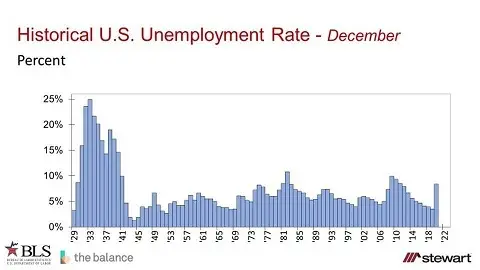

Historical U.S. unemployment rates are shown in the next graph for just the month of December each year commencing in 1929 – immediately prior to the great recession. The unemployment rate climbed from 3.2 percent in December 1929 (despite the stock market crash in September and October of that year), to 24.9 percent as of December 1933. At that time, however, the support for the unemployed came from the New Deal, which from 1933 to 1939 created temporary jobs for the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corp.

Unlike the periodic jobless peaks seen since 1929 and despite the 60-day spike in the unemployment rate from 3.5 percent to 14.8 percent (February to April 2020), those unemployed in the latest COVID-caused recession saw the best economic safety net in U.S. history – which historically never existed to the extent prior to the Coronavirus downturn. Just as the cost of living varies across the country, likewise do unemployment benefits.

State Unemployment Benefits and Comparative Ranks – 24/7 Wall Street

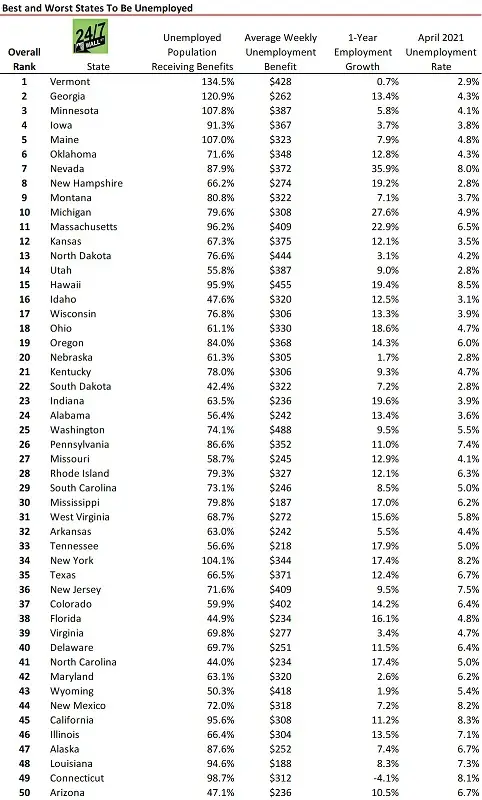

Current state-level unemployment benefits (excluding federal weekly payments) were analyzed by 24/7 Wall Street to rank the _Best and Worst States to be Unemployed based on state-specific data from April 2020 to April 2021. To rank states, 24/7 Wall Street created an index based on four metrics:

- Unemployment Recipiency Rate – the Percentage of Unemployed Individuals Receiving Unemployment Insurance Benefits

- Average Weekly Unemployment Payments as a Percentage of Average Wages

- One-Year Employment Growth as of April 2021

- Unemployment Rate as of April 2021

Their findings are detailed in the following table. According to the 24/7 Wall Street methodology, Vermont is the best state – benefits and employment wise – to be unemployed. Across the unemployed in Vermont, 134.5 percent receive state unemployment benefits. The average weekly state unemployment benefit is $428 – more than the $187 weekly in Mississippi and $188 in Louisiana. The worst state is Arizona where less-than-one-half of all unemployed receive benefits (47.1 percent). Four states had more people receiving unemployment benefits than the BLS counted as unemployed: Vermont, Georgia, Minnesota and Maine.

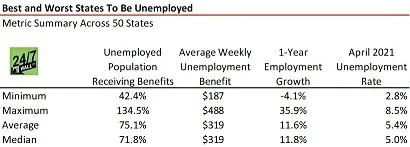

A summary of differences in the metrics are shown in the next table. Mississippi’s weekly benefit is just 38.3 percent of the payment received by those in Vermont. According to 24/7 Tempo, a subsidiary of 24/7 Wall Street, the cost of living in Mississippi is 15.6 percent below the national average (the lowest in the U.S.) while Vermont’s is 3.1 percent greater. Therefore, the comparative cost of living in Mississippi is 18.1 percent less, but weekly unemployment benefits are 38.3 percent less. Conversely, Vermont unemployment benefits are 129 percent more than Mississippi’s, but the comparative cost of living is only 22.1 percent higher.

Federal Weekly Unemployment Benefits

States administer the weekly unemployment benefits, which have typically been limited to 26 weeks. In the Great recession, Congress increased benefits to those with children and extended payments up to 99 weeks almost four times the historical duration.

This changed significantly in March 2020, with the signing of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) that vastly expanded unemployment benefits to millions – including many not ordinarily eligible. For most, in addition to the weekly state-administered unemployment benefits, recipients were also paid $600 extra – expiring July 31, 2020 (but due to administrative rules ending July 25th for some states).

An added $300 weekly benefit payment started on December 26, 2020, and was originally set to last 11 weeks, but was extended through September 6, 2021 by the $1.9 trillion American Recovery Plan (ARP).

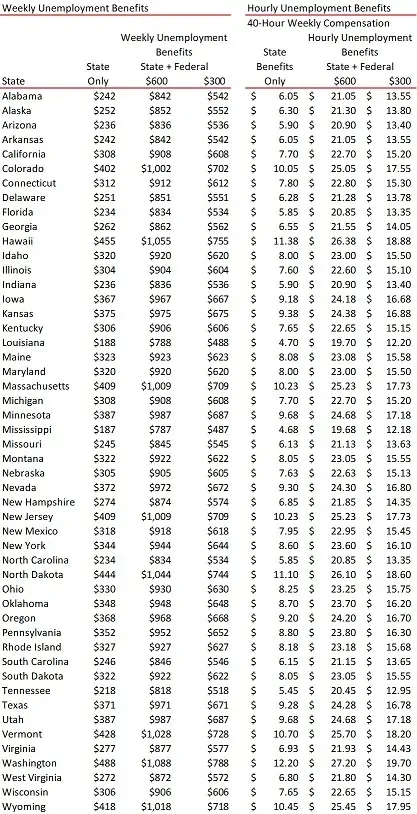

Weekly and effective hourly benefits for the unemployed are shown in the next table for the state only, state plus $600 federal payment, and state plus $300 weekly federal payment. None of these include the $1,200 one-time stimulus check resulting from the CARES Act (an estimated 160 million people) or the $1,400 ARP funded direct payment (to 167 million). Those two lump-sum payments raised the effectively hourly benefit or wage by $1.25 assuming 40-hour work weeks and 52 weeks per year. These are not adjusted for the 26 states which are planning or have already terminated the $300 weekly federal payment to the unemployed in hopes of motivating many to return to the workforce. Assuming the state plus $300 weekly unemployment benefit, 33 states were paying more than $15 per hour to the unemployed based on 40 hours per week, greater than the hoped-for federal minimum wage target by the Biden Administration.

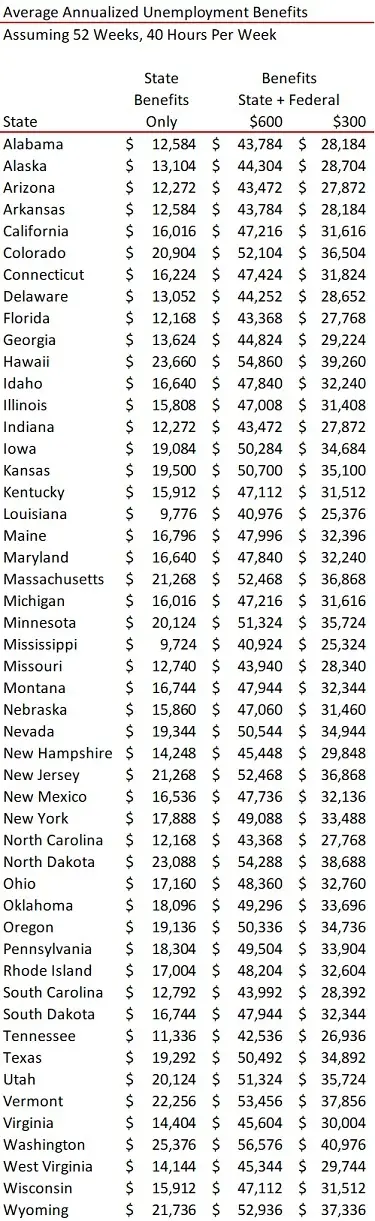

The last table shows annual compensation per person receiving unemployment benefits as if these payments extended across 12-months – neither including the two, one-time lump sum payments of $1,200 and $1,400 from the CARES Act and ARP, respectively.

While some people may be reluctant to return to the workforce due to medical issues or fears, no doubt many others have yet to return to work since they are near, as well, or better off economically when compared to working. Note these metrics are all based on one person, with the typical household in the U.S. having 1.2 employed workers per household. Hence the per=household unemployment benefits should receive a similar multiple.

With a record 9.3 million open jobs, the economy needs people to return to work.

Ted